The camel grows long eyelashes, thick thistles to break the wind that blows biting sand as a mist over the black deserts of Central Asia. Heavy metal through his nose, a ring holding a rope forward and back which connects him to the caravan. Somewhere in the middle, hundreds of animals move slowly under the sun, with skin leathery and dry. Clatterings of bells, to betray them after drifting off at night, and the sounds of nothing else besides. The heavy packs betray not their content, wrapped under brown and earthen cloth, but the spices and silk that lay hidden there will turn to gold before the moon wanes and transform the few muttering Arabs at the head of the caravan into men of wealth.

Moving mostly at night to evade the burning sun, with fires atop towers at the horizon to guide them. The trading towns on the Silk Road light beacons after dark to attract the Arabs like moths to a flame. They arrive exhausted but not gladly, for city folk practise different customs, and are never to be trusted. Still, now they might do well to think twice, Khiva is not just one town among countless others.

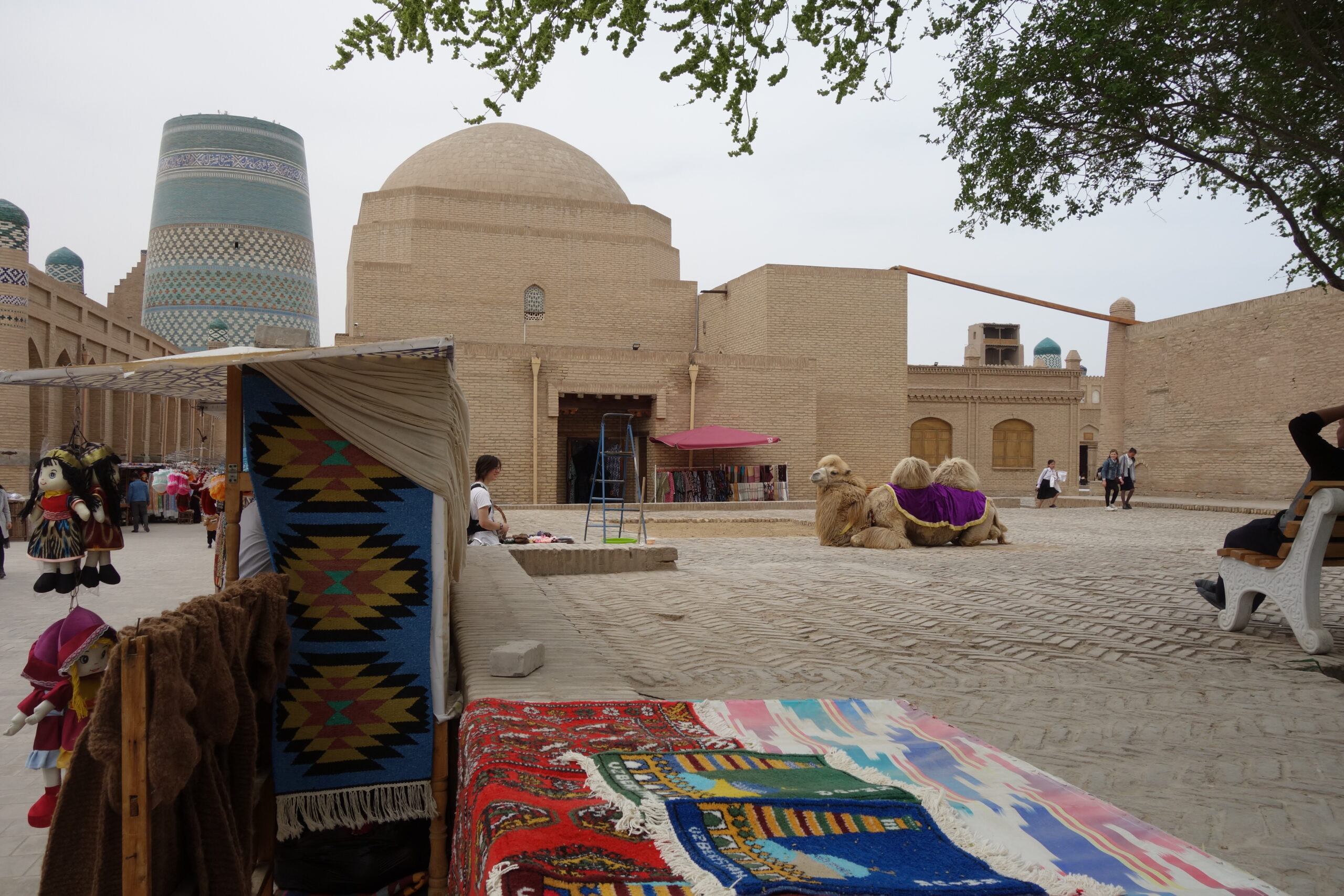

The ancient core of the city, hidden behind immense, crenellated walls built from packed earth and straw by slaves that spent exhausting and short lives here, hides the great square where until early the previous century tens of thousands of Russians and Persians were sold as servants. Stories of public executions, heads on the stake, bonfires for the infidel.

But more than this, Khiva is the background for many a scene captured in the Arabian Nights, with its dusky mosque, carried by 112 wooden pillars, robbed during raids across the East, and therefore to the last unique. Spreading out from this central point follow blue domes over long dead holy men, the walls clad in complex and infinitely repeating patterns.

Nearer the gates we find the royal palace on one side, with great audience halls for weary citizens, a harem once filled with diverse women, a new one every day if the khan so desired. And the khan, himself a descendant of the legendary Ghenghis, when not out plundering the Turkmen or Russians, lived in unrivalled opulence, enabled by the tax on fabrics and spices, brought here by the caravans.

The other side supports his citadel, crowned by toothy battlements around a sturdy watchtower. The flat desert affords a long view, and an early warning against raiders from beyond the red horizon. Behind stands the dazzling Kalta Minor, intended as the tallest minaret under the heavens, but suddenly cut short by the passing of the khan, and unfinished by his sons.

Unchanged since then, magnificent and old, with a style of its own, but without pretension of distinction.