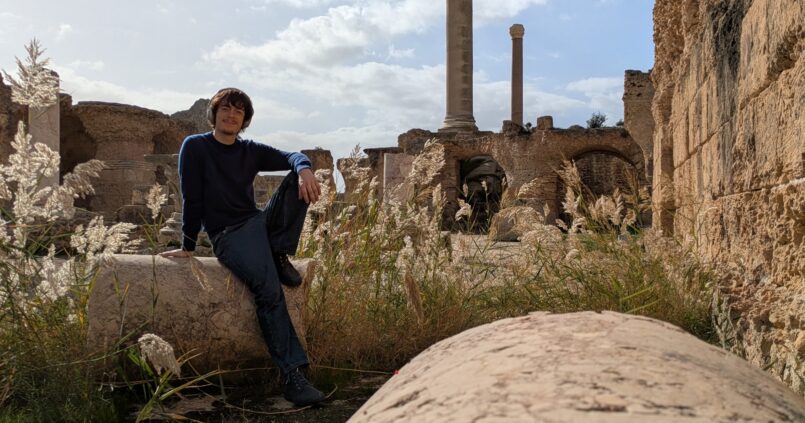

On a two day visit to the Eastern stretch of the Magreb, where the Atlas mountains dive into the Mediterranean and host the capital of Tunis upon the bay, I hoped to investigate the dream of Roman Senator Cato the Elder. Any debate in the senate he would end by stating that ‘furthermore, I believe Carthage should be destroyed,’ referring to their longstanding enemy, which under the leadership of Hannibal had once led hundreds of elephants across the Alps to ravage the Roman Republic.

I can quite definitively confirm, Carthage appears fully and wholly destroyed, and Cato need no longer worry. Not much more than foundations bearing no loads have been unearthed from the dust. Mostly shattered bricks and shards of pillars remain where once magnificent palaces, opulent temples and their redolent riches had overlooked a port flocked with merchants and their vessels packed with gold, pigments and grain.

Having arrived at this third paragraph, I realise I have now ruined my chances to further my own narrative, and to salvage any hopes for this text, I had better switch topics.

A day later I found myself strolling through the Souks of Tunis, where because of the soft rain, most townspeople had fled inside their white and blue homes, with only cats in their hundreds scurrying around the bazaar. The breeze carried perfumes of spices and herbs through the shady halls. Between the shops presenting natural soaps, leather shoes and traditional medicines, I spotted a small stall with intricate tiles, handmade cups and other beautiful earthenware. The owner invited me to take a closer look.

Politely I refused his offer of tea, but he sat me down nonetheless among the dyed carpets and started talking. Four generations ago, his forebears moved to the city, leaving behind the Southern deserts where Touareg traders clad in aquamarine transport ivory and gold across the Sahara. But almost uniquely in the country he still spoke the Amazigh language, once the common tongue of the people, but increasingly replaced by Arabic, to the point his skills were rusting, as he rarely had the chance to converse with anyone.

And he explained, although the language might be withering, the stories of his oral culture, told to him as a kid by his grandparents, still remain vividly in his mind, tales of humour and wisdom, of history and meaning. He forcefully refused my suggestion to write them down, as doing so would be a disservice to the tradition, confronting me with my own identity as a pen pusher.

He pulled books from the shelves discussing genetics and linguistics, describing the origin of the Tunisian people, after immigration waves over the millennia from all across the Mediterranean, sometimes switching to his native language to order his thoughts before furthering in French. He seemed to know everything, and grateful at the opportunity to relate his favourite pieces of knowledge to an outsider, overwhelmed by choice and therefore stumbling chaotically and rapidly from topic to topic.

Only because my flight back home drew near did I depart his enthusiastic voice. Otherwise I would have stayed to listen til the sun set and in turn the moon shone over the Minarets and fluttering flags upon the citygates of Tunis.

Comments (2)

En natuurlijk waren de katjes het allerbeste

Honderden! Mogelijk zelfs duizenden o.o